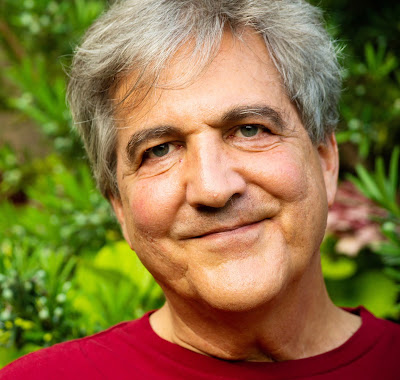

(Photo courtesy of Wesleyan University)

I first encountered Ron Jenkins' work because I was researching the 1971 Attica Prison uprising and saw that he was hosting an event commemorating the 50th anniversary. The presentation (only his latest prison/university collaboration) featured the voices of recently-incarcerated individuals as well as Wesleyan students and commentary from two survivors of the events in Attica. Turns out, Professor Jenkins is chairman of the Theatre department at Wesleyan University and a visiting Religion and Theatre professor at the Yale Divinity School, Institute of Sacred Music. He uses documentary theatre to promote social transformation and human rights, and has led workshops around the world. He is also a former circus clown. If you’re interested in reading some of my other work on criminal justice and prison reform, check out these posts: “Locking Up Our Own” by James Forman, Jr., Yukari Kane: Volunteering at San Quentin, Covid-19 at San Quentin (Joe Garcia), Racism in Prison (Jesse Vasquez) and Newspaper Run by Prisoners Offers New Chance (published in News Decoder).

I read somewhere that you started your professional theater career as a clown. How did you go from juggling in a circus to teaching theater to students in colleges and prisons? When and how did you first become interested in what was happening behind prison walls? When did you first start teaching theater to incarcerated students?

Before working in the circus, I was a teacher in day care-centers and worked with autistic children in Bellevue Hospital in New York, where the only way to communicate with the severely challenged patients was to communicate with them non-verbally, so my impulse to go to clown college and perform in the circus grew out of those experiences and my desire to connect with children through laughter. My teaching in prisons and colleges (where I bring students to prison to create performances in collaboration with incarcerated men and women) gives me a different opportunity to use theater as a catalyst for transformation in non-traditional settings.

Some of your work has involved both incarcerated students and students from well-known colleges like Wesleyan and Yale. What do these two very different groups learn from each other? Which is most transformed by the experience? Any unexpected anecdotes you might share?

Everyone involved in those collaborations is transformed in different ways. It all depends on how open each individual is to transcending their preconceptions. Yale and Wesleyan students are exposed to an environment of institutionalized racism that is beyond their previous experiences. Incarcerated students come to understand that their intellectual and analytic abilities are no different from those of students from elite colleges. And I learn something about the texts we study and the power of theater that goes beyond anything I have encountered in performances outside of prison.

You have used Dante’s Inferno as the jumping off point for some of your work in prisons. When did it first occur to you to introduce Dante to incarcerated students? What kind of reactions did you get from other professors when you first told them of your plans? What have you learned over the years about helping incarcerated students connect with writers who died centuries ago?

I first became intrigued with Dante's text when I was invited to stage excerpts from "Inferno" at the Gardner Museum of Art in Boston in 2003. The cast consisted of performers from Italy, Cambodia, Indonesia, and Turkey and I was amazed by the audience's rapt responses to their diverse interpretations of the poem. I was also spellbound by the lectures given by Dante scholars as part of the Gardner event, particularly a lecture by Yale Professor Peter Hawkins. Until that time I had been teaching Shakespeare in my prison theater workshops, but when I tried working with Dante I sensed that the connections were even deeper, especially because Dante himself had been convicted of crimes and wrote his poem in exile from his home and family under a death sentence, knowing if he went back to Florence he would be burned at the stake. Those facts helped men and women in prison identify with Dante's story about a journey out of hell. One of the men who took my Dante workshop in Sing Sing used a quote from Inferno in his successful application for clemency and credits Dante's words for getting him out of prison.

What are some of the most innovative or promising arts or education initiatives in prisons today?

The most promising prison arts initiatives I have seen take place in Italy where attempts are made to use theater to integrate prisons more fully into the communities where they are built. Audiences from the community come into the prison to see plays, and incarcerated performers are often allowed to leave the prisons to perform out in the community. This is very different from the situation in the U.S. where prisons are hidden away and the people who live there are erased from society.

What role should colleges and universities play in supporting the incarcerated?

More colleges and universities like Wesleyan and Yale are developing prison education programs. I hope they will be expanded to include support for graduates when they leave prison.

Is there anything you wish Americans understood better about mass incarceration and life behind prison walls?

Only that people in prison are human like everyone else, and most of us have made the same or similar mistakes but don't go down the path to incarceration because of the privileges we enjoy that most people in prison do not have, particularly those who come from communities of color who make up the majority of the population behind bars.

Think back to when you were 17. What did you want to be when you grew up?

I wanted to be a child psychiatrist, which is how I ended up working at Bellevue before dropping out of college to join the circus.

If you could travel back in time, what advice would you give to your 17-year old self? Is that the same advice you would give me today?

I would tell myself not to be afraid to take risks that involve giving up security in the pursuit of the unknown. I did not take that advice until I was 20 and began taking risks like dropping out of college to study clowning in Mexico (without knowing Spanish), going to live for a year in an Indonesian village to study masked theater (without knowing Indonesian), and taking a break from graduate school to follow a clown around Italy, Dario Fo, who eventually won the Nobel Prize in Literature (without knowing Italian). Looking back on the last sentence I would also tell myself to spend more time learning languages, because when I finally did learn to speak Indonesian and Italian (my Spanish never progressed very far because the clowns I worked with there performed without words) new worlds of possibilities opened up that transformed the way I understood, practiced, wrote about and taught theater. And yes, I would give the same advice about language-learning to any seventeen-year-old today, but I wouldn't want to take responsibility for giving the advice about taking risks to leap into the unknown to anyone. That is advice you can only give to yourself when you feel the time is right.

|

| Professor Jenkins with incarcerated students in a theater workshop he directed in Indonesia's Kerobokan Prison. |

Comments

Post a Comment